I benchmarked 6 PDF engines — the fastest is not the one I’d pick

Categories: Development

I’m building a typesetting engine for a living (speedata Publisher). People keep asking me “why not just use Typst?” or “isn’t WeasyPrint good enough?” and I never had a good answer with real numbers. Just gut feeling. So I decided to actually measure it.

I set up a simple benchmark, same document with all six tools. And what I learned was maybe not what I expected.

The setup

The task is simple: a mail merge. You have an XML file with name and address records, you fill in a letter template, and you get a PDF out. One page per letter, with a logo, sender info, recipient address, and some body text. Nothing special, really every tool should be able to do this.

I tested with 1 record and with 500 records. All templates produce more or less the same visual output. Same A4 page, same Helvetica (or the similar TeX Gyre Heros clone), same logo, same layout with the sender on the right side and body text at 105mm width with hyphenation turned on.

The tools:

- speedata Publisher (sp) — my own engine, written in Go, Lua which uses LuaTeX in the background

- Typst — the new kid, written in Rust, has native XML support

- pdflatex — the classic, with Python/Jinja2 for the templating

- LuaLaTeX — basically pdflatex but with Lua scripting and a more modern font system, also with Python/Jinja2

- WeasyPrint — HTML/CSS to PDF, Python based

- Apache FOP — the enterprise XML/XSL-FO thing, Java

All benchmarks ran with hyperfine on a macBook air M4 (16 GB). You can find the full setup on GitHub if you want to try it yourself.

The numbers

1 page

| Tool | Time | Relative |

|---|---|---|

| sp | 95 ms | 1.0x |

| Typst | 106 ms | 1.1x |

| pdflatex | 329 ms | 3.5x |

| WeasyPrint | 335 ms | 3.5x |

| LuaLaTeX | 519 ms | 5.5x |

| Apache FOP | 532 ms | 5.6x |

With one page, sp and Typst are basically the same. Both under 110ms. Everything else is 3.5 to 5.6 times slower.

500 pages

| Tool | Time | Per page | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typst | 157 ms | 0.3 ms | 1.0x |

| pdflatex | 712 ms | 1.4 ms | 4.5x |

| Apache FOP | 1.6 s | 3.2 ms | 10x |

| LuaLaTeX | 2.4 s | 4.7 ms | 15x |

| sp | 4.4 s | 8.7 ms | 28x |

| WeasyPrint | 8.7 s | 17.3 ms | 55x |

OK so this is where it gets interesting. Typst does 500 pages in 157 milliseconds. That is not a typo. Once it is running, it spends about 0.3ms per page. sp, which was basically equal at one page, needs 4.4 seconds — 28 times slower.

At one page they are tied, at 500 pages it is not even close. Typst has maybe 60ms startup cost, and after that it just flies. The per-page cost of sp is roughly 28 times higher.

Also worth noting: WeasyPrint really does not scale well. It goes from “ok” at one page to “maybe go get a coffee” at 500. pdflatex on the other hand scales surprisingly well — the per-page cost is only about 0.8ms if you subtract the startup.

So if speed is all you care about, just use Typst, right?

But look at the actual output

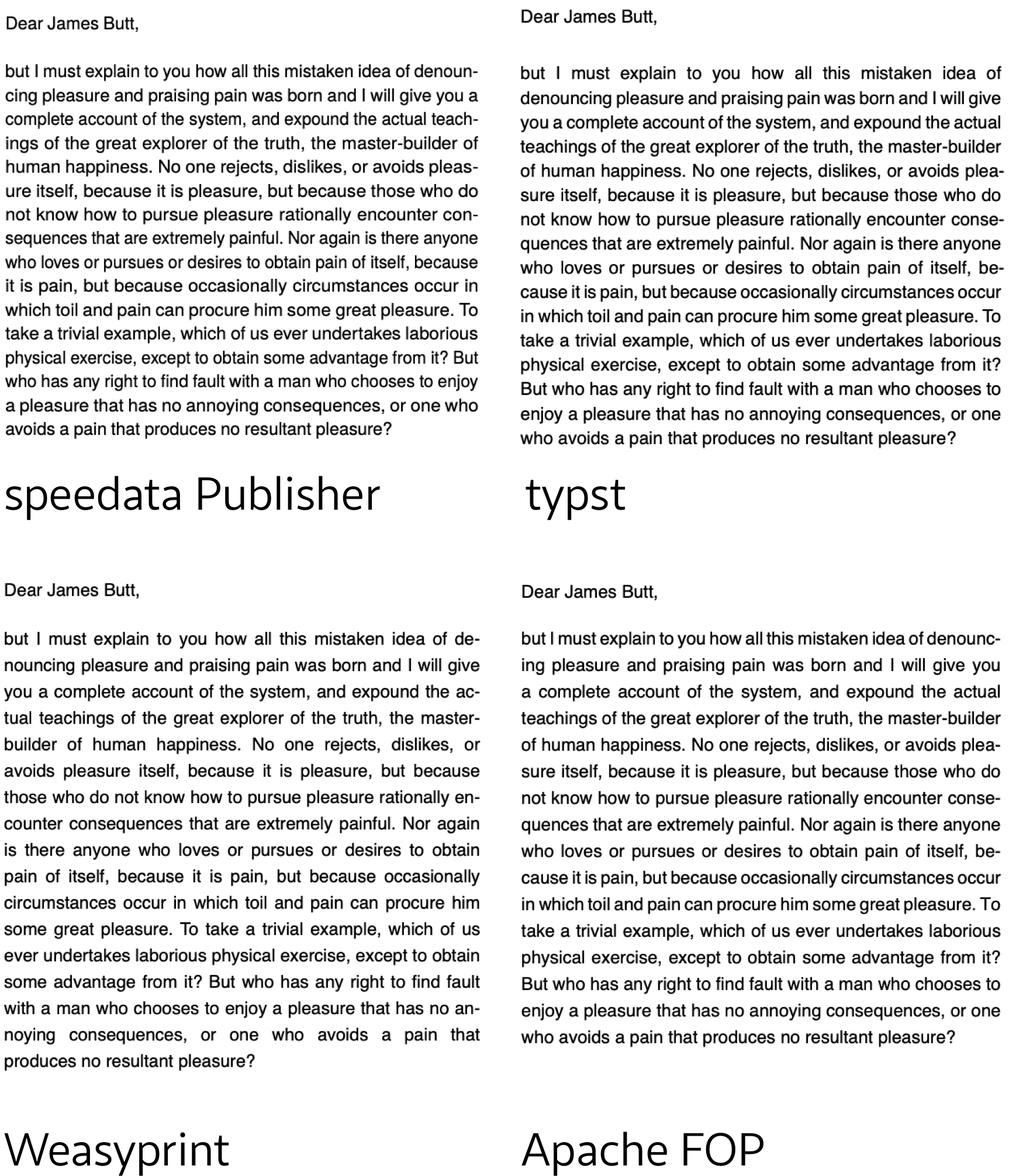

This is where it gets more complicated. Open the PDFs next to each other and look at the body text:

You see the difference? The justified text looks different. Not because of different fonts — the decisions are different. Where to break the lines, where to hyphenate, how to distribute the whitespace.

pdflatex and sp use algorithms based on Knuth & Plass (the TeX line breaking algorithm). They look at the whole paragraph at once and find the best set of breakpoints for all lines together. The result is even word spacing, no rivers of white, and good hyphenation.

Typst, WeasyPrint, and FOP seemingly use a much simpler algorithm. It looks like they go line by line from top to bottom and decide for each line separately. This is faster — and that is probably part of the reason why Typst scales so well. But you can see it. Some lines are too loose, some too tight. Hyphenation sometimes feels a bit random.

Edit Typst’s author has clarified: “However, one thing we noticed is your assertion in the justification section that Typst is not using Knuth-Plass – we do, by default when justification is enabled. The only thing of the original paper we don’t implement are tightness classes to prevent a very tight line and a very wide line directly next to each other.”

For a simple letter, honestly both are fine. But try a narrow column with a technical text full of long words, and then you really see the difference. The Knuth-Plass output looks like a properly typeset book. The first-fit output looks like a web page that somebody printed.

A benchmark cannot capture this.

What benchmarks cannot measure

Here is what actually matters in production, and it has nothing to do with milliseconds: what happens when the content does not fit?

Think of a product catalog. Each product gets one page: a data table at the top, product photos at the bottom. Simple enough. But then product number 47 has a table with 30 rows instead of 10. Now what?

In Typst, you can use measure() to get the height of the table and compare it with the available space. That is a reasonable approximation. But Typst cannot do a real trial layout across page breaks — it measures content in a single frame only.

In the speedata Publisher, you can do this:

<SavePages name="attempt">

<PlaceObject>

<Table>...</Table>

</PlaceObject>

</SavePages>

<Switch>

<Case test="sd:number-of-pages('attempt') > 2">

<!-- does not fit — shrink font, split differently, whatever -->

</Case>

<Otherwise>

<InsertPages name="attempt"/>

</Otherwise>

</Switch>

This is real trial typesetting. It actually lays out the full content, with real page breaks, counts how many pages it needs, and then you decide: keep it, or throw it away and try with different settings. No other tool in this benchmark can do that.

Is this slower than just going through the content without looking back? Of course. And maybe that is part of why sp is 28 times slower at 500 pages — it is built for careful layout, not for fast layout. But the alternative is that a human opens each PDF and manually checks if page 47 looks right. That is not a millisecond problem, that is a “you need to hire someone” problem.

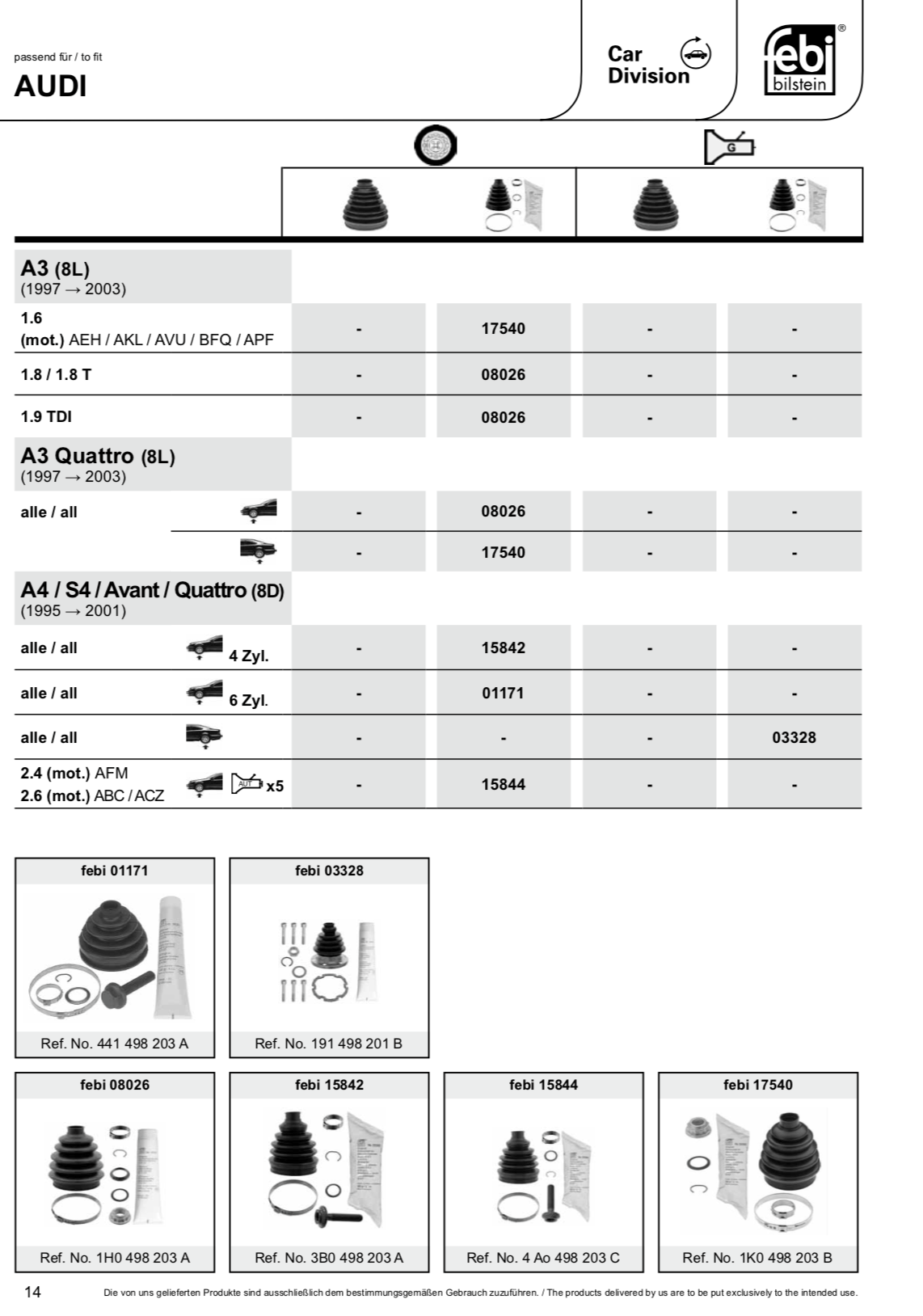

A real-world example: the product catalog page

Here is an actual page from a spare parts catalog, built with the speedata Publisher. This is a very typical use case for a product catalog.

Look at what is happening on this page. The data table grows from top to bottom — model by model, row by row. The product images at the bottom grow from bottom to top, in rows of up to four. The table and the images share the same page, and neither is allowed to overlap the other. The number of table rows varies per page, the number of product images varies per page, and the layout has to figure out on its own how to divide the available space.

This is not a fixed template. It is an adaptive layout. The engine places the table, measures how much room is left, and fills the remaining space with as many product images as will fit — bottom-aligned, in rows of four. If a page has fewer products, you get two images in the last row instead of four. If the table is longer, the images get pushed to the next page. All of this happens automatically, without a human touching any page.

How would you do this with the other tools?

In Typst, you could get close. You would measure() the table height, calculate the remaining space, and manually arrange images in a grid at the bottom. But you are doing layout math by hand, and if the table happens to break across pages, things get complicated fast. Typst has no built-in way to say “fill the rest of this page from the bottom up.”

In pdflatex or LuaLaTeX, you enter the world of TeX float placement — \vfill, \bottomrule, maybe a minipage at the bottom. For a single page with a known table height, you could hack something together. But for hundreds of pages where the table height varies? You would likely write a Lua callback in LuaLaTeX that inspects the page after layout and inserts the images. Possible, but painful.

In WeasyPrint, this is essentially not possible. CSS has no concept of “fill the remaining page from the bottom.” You would have to pre-calculate the table height outside of the rendering engine and generate custom CSS per page. At that point, you are not really using a layout engine anymore — you are the layout engine.

In Apache FOP, XSL-FO has some support for this kind of thing with region-after and fo:block-container, but in practice FOP’s implementation is limited. You might get a rough approximation, but the automatic “grow from bottom” behavior is not something FOP handles well.

In the speedata Publisher, this is roughly a dozen lines of layout XML. Place the table, ask how much space is left, arrange the images in the remaining area. It is exactly the kind of problem the tool was built for.

The difficulty ladder

The real comparison is not “which tool is the fastest at a trivial task.” It is “which tool can even handle the task.”

| Task | Typst | sp | WeasyPrint | FOP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple mail merge | fast | fast | medium | slow |

| Justified text quality | ok | excellent | ok | ok |

| “Does this fit on 2 pages?” | approximate | exact | no | no |

| Dynamic layout fallbacks | manual | built-in | no | limited |

| 200-page product catalog with conditional layouts | in theory | core use case | no | sort of |

For a mail merge, use Typst. Seriously. It is fast, the source files are nice to write, and the output looks good enough.

But once your layout needs go beyond “fill in a template, output PDF” — once you need the software to actually make decisions — things change. And that is where tools like sp become worth it, even if they need a few hundred milliseconds more per page.

What I actually learned

I went into this benchmark hoping that sp would be fastest at everything. It is not. Typst is 28 times faster at 500 pages, and I cannot really argue with that — they have done amazing engineering work.

But I also realized that the benchmark I set up — a simple mail merge — is exactly the kind of task where the strengths of sp do not show up at all. It is like you compare a sports car and a pickup truck on a flat highway. Sure, the sports car is faster. But that is not what you bought the truck for.

The right question is not “how many pages per second.” It is “how many pages until you need a human to check.” And that is much harder to measure.

The complete benchmark setup (all templates, scripts, and data) is on GitHub. Run ./benchmark.sh to reproduce on your own machine.